Günter Wallraff: “The gaps were unbridgeable even before Corona”

At 83, he still provokes. A conversation about cultural appropriation, gender language, the AfD, the coronavirus, and the question of how much rapprochement journalism can dare to take.

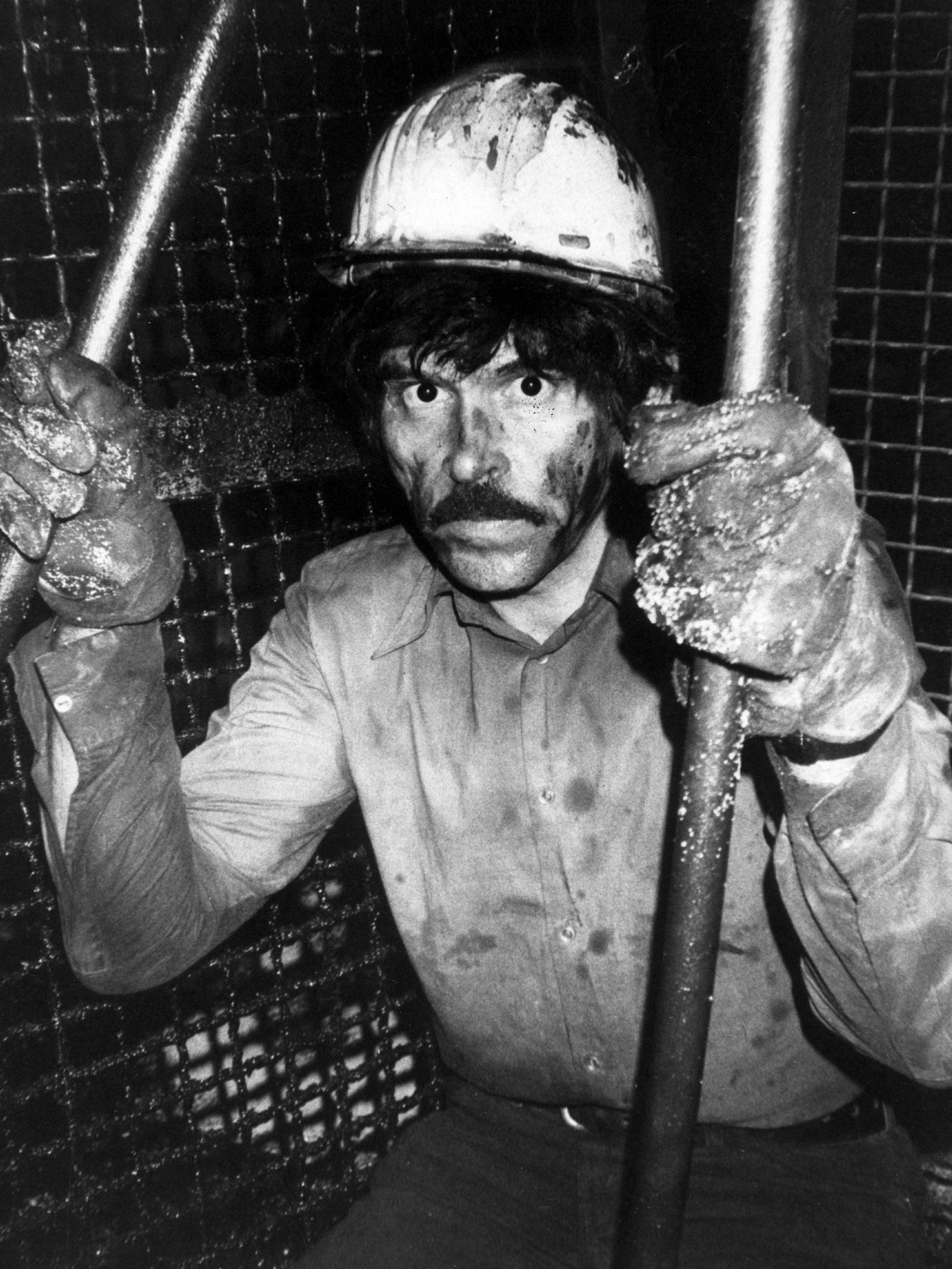

On October 21, 1985, "Ganz unten" (At the Bottom) was published. Exactly 40 years ago, undercover journalist Günter Wallraff published what remains Germany's most successful non-fiction book to date, with a circulation of over five million copies in German alone. The book was the result of undercover research for which Cologne journalist Günter Wallraff disguised himself as the Turkish man Ali and worked in steel mills, on construction sites, and at McDonald's. It has been translated into 38 languages and read even in countries that had no significant labor migration. Wallraff is now 83 years old and lives in the Cologne district of Ehrenfeld in a house with a rear annex where his grandfather made pianos. As he scribbles a parting dedication in his book, he says: "It looks like this now because I write standing up, not because I'm senile or anything." In fact, nothing could be further from the truth: Wallraff is obviously mentally and physically fit. He wins every game at the ping-pong table, to which he invites all visitors.

Mr. Wallraff, why did you work in factories back then?

My first industrial report was "On the Assembly Line" at Ford. My father had ruined his health there in the so-called paint hell because there was practically no health protection there at the time. I applied and was desperate to start on the assembly line. The personnel department was well-intentioned by me: "You went to high school, why do you want to work on the assembly line? You can start in an office, you'll get better pay there, only foreigners work on the assembly line." I insisted on working on the assembly line and published my first industrial report about it. Looking back, I have the Bundeswehr to thank for helping me find my role in society and develop the potential for resistance. I was drafted anyway as a conscientious objector, back when the Nazis were still in charge. People sang Nazi songs, there were anti-Semitic slogans, and the trivialization of the Holocaust . I lasted ten months there. I refused to touch a weapon and came up with a few ideas to counter the drill and blind obedience: When everyone rushed to their guns in the morning, for example, there was a wildflower stuck in each muzzle. Great laughter.

They let you get away with that?

They tried every method to break my will. When the Bundeswehr noticed that I was writing a diary and that the magazine Twen wanted to publish it, they offered me immediate release. However, they stipulated that I would not publish anything about my ten-month period of service in the Bundeswehr! I refused. To undermine my credibility, I was then admitted to the closed psychiatric ward of the Bundeswehr hospital in Koblenz. After a week and a half, I was released with a fitness level of VI ("abnormal personality, unfit for peace and war"). At the time, it was an irritation, but today it's an honor for me. I had previously completed my apprenticeship as a bookseller, but now the idea of pursuing this profession was a complete no-brainer.

Where did the desire to disguise oneself and become someone else come from?

This was a necessity. Even back then, companies tried to prevent my publications, so they initially appeared under the pseudonym "G. Wallmann," because I could still apply under my own name. Then I became too well-known and had to obtain other working documents. My work was repeatedly accompanied by lawsuits, for years, by Springer and the Strauss consorts. They tried to criminalize my work. The Federal Court of Justice finally ruled: When serious abuses are involved, the public has a right to be informed, even if the findings are obtained under a different identity. Therefore, through the so-called "Lex Wallraff," undercover operations like "Team Wallraff" and "wallraffen" at RTL are still legitimized by the Federal Court of Justice and the Federal Constitutional Court to this day.

In the case of “Ganz unten” you wanted to convey what it feels like to be a guest worker in Germany.

I live in Cologne-Ehrenfeld, a district where one in three or four people is an immigrant. Neighbors spoke of degrading working conditions, but they were afraid of losing their jobs. I had already made my first attempts as a Turkish worker over ten years earlier. Covert recordings of me looking for work and disguising myself had already been made. But I failed the intensive Turkish course. At some point, I said to myself: Now or never! I placed an ad: "Foreigner, strong, looking for any kind of work" and ended up in work crews. I didn't know what to expect, but I felt an existential need to experience it firsthand. But my Turkish language problems persisted: When my Turkish colleagues asked me why I didn't speak Turkish, I claimed I was raised by my Greek mother, separated from my Kurdish father at an early age. A suspicious colleague eventually demanded, "Speak Greek!" And lo and behold, I remembered the beginning of the "Odyssey" in ancient Greek, because I had Greek classes in high school alongside Latin. You never learn for nothing in life.

I feel closer to the marginalized

Has a certain fearlessness always characterized you? You've received death threats, and anyone could find out where you live.

As a child, my mother encouraged me to be a well-adjusted person, and I was always plagued by self-doubt. As an only child, I was rather shy and introverted. At some point, I began to dwell on these fears. I've since developed a certain sense of belonging, precisely because I've exposed myself to these issues. I feel like a stranger in a society where many things aren't right. And I feel most closely connected to those who don't belong. It's simply easy for me to step back and thus empathize with others. In each role, I'm more identical, more alert, and more capable of learning.

Is it also your personal merit that conditions have improved, for example working conditions in steel plants?

That was a huge encouragement at first: "Right at the Bottom" had immediate effects, initially at the crime scenes. Together with colleagues at Thyssen, we held a go-in in the human resources office and demanded that the colleagues from the temporary employment agencies be given permanent positions. We succeeded. The chairman of the general works council, who had allowed all this to happen, was forced to resign and was later expelled from IG Metall. Thyssen was fined millions. From then on, dust masks and hard hats were mandatory, continuous shifts were abolished, and a dozen safety engineers had me to thank for their hiring. The Minister of Labor and Social Affairs (SPD) set up a working group, known internally as the "Ali Group," a mobile task force that from then on controlled the corporations.

What you describe in "Ganz unten" is a kind of wage slavery. Doesn't that exist anymore?

It has shifted.

Who are the Turks of today?

For example, the workers who come to Germany as migrants from Eastern Europe, Romania, Bulgaria, or Africa, who are forced to work under extremely precarious conditions, even resulting in death. Such as the still-unsolved death of 26-year-old temporary worker Refat Süleyman, whose body was found in the mud of a slag pit on the grounds of the ThyssenKrupp steelworks.

A philosophical question: Can one really experience what it is like to be someone else while wearing a disguise?

When I'm in a role, I'm almost identical—I'm a different person and sometimes even dream at night in my new identity. Therefore, the accusation of "cultural appropriation" is a superficial point of view in my case.

So you would say that it is permissible for a representative of the white majority society to dress up as a Turk or even as a Black person?

Anything else would have been a professional ban for me. What I did wasn't an appropriation, but an approach. I was "Ali" for two and a half years and severely damaged my bronchial tubes in the factories; I got through it together with my colleagues. Or when, weeks after leaving my role as a Black person, I crossed the street because right-wing radicals were passing me, it showed me: the role had become a part of me. Even when I was a parcel driver for GLS with my German-Afghan colleague Augustine F. – getting up at 4 a.m. and working 12 to 14 hours until I was exhausted – I became a different person.

So should every white person put themselves in such a role to learn what racism really means?

This isn't a principle that can be generalized, although such a change of perspective would benefit some from the upper or upper middle classes and broaden their horizons. That's why I'm also in favor of a year of social service for all young men and women. But for me, it's something very personal, something that has to do with me and my search for identity. "Participant observation" has long been recognized and highly regarded in research and academia. In Germany, class society is increasingly developing into a caste society, in which access to education and social participation is increasingly dependent on social background.

Did you ever want to change classes while researching “At the Bottom”?

No, I came from a rather poor background myself. My father died at the age of 59, when I was 16, and I had to work as a student to help support myself.

Did the criticism of “cultural appropriation” hurt you?

Accusations of cultural appropriation, or whatever you want to call it, don't affect me. Those trying to cancel me were individual German pseudo-intellectuals trapped in their own bubble. Back then, after the publication of "Ganz unten," I received thousands of letters, especially from immigrants, who told me: Finally, a German has experienced this and exposed it, no one listens to us, no one believes us – you're one of us. This continues to this day, even into the grandchildren's generation.

What do you say about the current discourses on identity politics – for example, that, in short, only members of minorities are allowed to speak for themselves?

That's narrow-minded, that's abstract, that doesn't do justice to the problems. I had a role model in my role as a Black person: John Howard Griffin. Griffin learned about the extremely high suicide rate among Black people in the southern United States and suspected racial segregation was the reason. To investigate this, he decided to conduct an experiment in 1959: Although it was a serious health risk, he took medication that changed his skin color so that strangers would mistake him for Black. In this role, he traveled through the southern states and experienced firsthand the humiliation of the white population and their extreme racism for weeks. After publishing his experiences, he was met with hostility and ostracism, so he emigrated to Mexico with his family.

'Ali' was not a role play – it was an existential change of perspective

Are you pleased that a Green Party politician of Turkish descent made it to the mayoral runoff in Cologne?

Berivan Aymaz, she would have truly been a global citizen for Cologne, someone who changed perspectives! We were in Turkey together and campaigned for political prisoners there. We know too little about Turkey. For example: Unlike here, the elderly there aren't put in nursing homes where they then rot away, especially in the profit-run homes. Instead, there are family structures where people are cared for as a matter of course.

Is this a topic you are currently working on: aging?

The topic remains relevant. Elderly people in nursing homes have virtually no lobby. Given my age, I would be practically predestined for this. This could be my ultimate role.

You're a leftist through and through, a critic of capitalism, and you describe intersectional discrimination in "Ganz unten" (At the Bottom)—that is, how a Turkish worker is discriminated against not only as a migrant, but also as a woman. What is your view of the so-called "woke movement"?

I constantly find myself caught between two stools: uncomfortable sitting position, but it's supposed to be good for my backbone, for example, by saying: I don't like this arrogant attitude, this claim to sole representation. Let's take our language as an example: I fundamentally think it makes sense for women to be made visible linguistically. But when it comes to everyday terms that have always been understood as gender-neutral... Most recently, everything inside me rebelled when a respected feminist colleague, in an interview with me, wanted to change the word "guest" to "guestin" and insisted on it. When it goes too far, it goes too far. When language is messed up and we force people to adopt something they can't understand, then that doesn't help at all. In the 1980s, there were efforts in professional circles and magazines to abolish capitalization and demand that lowercase letters be used throughout. However, this supposed dictate of progress failed to prevail. A similar fate could befall gender in due course. The generic masculine in its original form is therefore unlikely to return, as the broad discussion about gender-fair language has, after all, profoundly sensitized us to linguistic inequality.

Another trigger topic: Did the undercover journalist Günter Wallraff ever secretly join a walk with lateral thinkers during the Corona period?

Yes, I wanted to learn more about it firsthand. It pains me that the positive connotation of the term " lateral thinker " has been lost and that it has now been claimed by and for people who are often simply stubborn and obstinate. However, in my opinion, the self-proclaimed lateral thinkers during the coronavirus pandemic are more confused and misguided, often without measure or balance. The then Health Minister Karl Lauterbach , with whom I am friends, probably saved many lives with his policies. The way he was and continues to be attacked for this is unspeakable. For this reason, he remains under personal protection to this day.

But one can also view his role during the coronavirus pandemic very critically: He tweeted constantly, constantly released new studies, and thereby stoked fear and panic. He certainly contributed to people becoming lonely or socially neglected.

I see it quite differently. I know him too well for that. It's thanks to him that, relatively speaking, fewer people have died in Germany than in other European countries. I've discussed this with him a lot. He feels committed to his own knowledge and conscience, and to science – and today he sees things in a more nuanced way. Unlike many others, he's willing to put assumptions into perspective and publicly stand by them.

Has the coronavirus caused lasting damage to the mood in the country, making the social divides unbridgeable, as is often said?

These were already unbridgeable before.

To return to "right at the bottom": Back then, you were the Turk Ali. Are Turks no longer right at the bottom today? Are they integrated, practically sitting at the table?

I have many friends of Turkish descent who have found their place within German society. Among them are true global citizens who are able to compare, embrace the positive aspects of each culture, and leave dogmatic and authoritarian attitudes behind.

Everyday, so-called structural racism can be very persistent.

After "Ganz unten" (Right at the Bottom) was published, I had to be careful. Nationalist-religious newspapers wrote that I now intended to convert to Islam – nothing was further from my mind. Instead, I traveled to Turkey, visited the Minister of Justice, and asked to be allowed to visit political prisoners. This was initially categorically rejected. Later, the Minister of Justice informed me that I could visit the prisons. I was able to secure prison relief for individual inmates, and I got an elderly prisoner who was mentally unstable released. Years later, in a broadcast on Deutschlandfunk, a representative of a Cologne mosque approached me in a different context, asking me to become a member of the advisory board. I made it a condition that Rushdie's book "The Satanic Verses" would then be discussed in this mosque. I owed that to Salman Rushdie, who had lived with me in hiding for a while after the fatwa. Initially, the mosque representative agreed to this, but was rebuffed by the Turkish authorities, who then publicly declared that I had "hurt the feelings of Muslims worldwide" with my request. I subsequently received death threats and requested police protection for my family. I am very sensitive to political Islam and Islamism .

In the local elections, the AfD received a very strong vote in the integration councils . How do you explain that? Are the migrants of the past so well integrated that they no longer have any desire for further immigration? That has to do with their social status. There are many workers among them, but also lower-level administrative employees or small service providers, protest voters who no longer feel represented by the parties and feel abandoned. People who do not earn much who see that they themselves are suffering from rising rents or food prices, for example. They are constantly confronted with cuts in the social security system. As a result, they experience the entire system as simply unfair and then partly project the causes onto the issue of migration. This is often a conglomerate of defiance, aberration, and protest.

Should one seek dialogue with AfD voters?

Not with the leaders and officials, it's not worth it. They pursue their one-sided, economically liberal, nationalist power agenda – mercilessly! But with the voters, yes, as long as they aren't die-hard neo-Nazis.

Has the SPD in particular done something wrong in this regard, so that workers no longer feel represented by it? This doesn't just affect the SPD. Overall, I see a disconnect between our democratic institutions and the needs and problems of most people. This fits with the state of the nation, in which the super-rich are getting richer and the poor are growing in number. The bottom half of the population – that is, 40 million people – owns just one percent of the total economic wealth. Conversely, the 45 ultra-richest families alone own more than all of these 40 million combined. The top ten percent of the population control almost 60 percent of the total wealth, while the bottom third is virtually destitute or in debt, and the trend is rising. According to statistics, the average life expectancy of men in the lower income group is about ten years lower than those with high incomes. This requires partisanship and a courageous commitment to the marginalized, as well as solutions and concepts that go beyond the arrangements of day-to-day politics. The following applies to all democratic parties: We should not forget that today's positive realities, such as women's equality, children's and minority rights, labor protection laws, and environmental protection regulations, were the often-mocked utopias and visions of the past. Our visions and demands today must become the reality of tomorrow so that there can still be a future worth living.

Do you have feedback? Write to us! [email protected]

Berliner-zeitung